Inner images and audible colours (synaesthesia)

In physical terms, I am completely blind. That means I can no longer distinguish any colours or light with my actual eyes. So I do not see any difference between day and night. But if you were to conclude that a profound darkness must have descended inside my head, you would be mistaken. Since the day I went blind in 1989, I have continued to experience inner vision.

When I talk about this ‘inner vision’, I mean that new images constantly form inside my mind. I do not have to make the slightest conscious effort for that to happen. These images simply arise spontaneously, fed by my other senses or the situation I am in at that moment. My inner images are not as sharp and detailed as they would be with eyes that worked properly, but they are still there and prove their usefulness time and again. For example, if I am walking through a city on my own, I orient myself on the basis of a mentally projected map, with which I can work out how best to get from street X to street Y. When I meet someone, I usually see their shape in light or dark tints. This is probably a visual representation of the impression that the person’s voice, behaviour and general character make on me.

You might compare this inner vision to what happens when we are reading a good story. All kinds of lively scenes may play out before our mind’s eye then as well. The imagination uses our previous experiences and memories as a kind of building block, but then recombines them to create new worlds where we have never been before. How else would we be able to travel from the earth to the moon with Jules Verne? Or learn witchcraft and wizardry with Harry Potter at Hogwarts? In my case, my mind undoubtedly also draws upon my visual memory for that constant flow of inner images, and it can still use it to create things, faces and landscapes I have never seen before , even after thirty years.

Besides my memory, however, there is another, more unusual ability that plays a role in forming my mental images. I didn’t find out I had this ability until I was about eight years old. In my primary school class, I had just typed a text on my Braille typewriter when I said something about the pretty colours on the typed sheet that was now lying in front of me on the table. My teacher was astonished: she explained that the sheet of paper was still entirely white. That is logical of course, because Braille doesn’t use a single drop of ink and the letters only consist of dots that can be felt on the white paper. Nevertheless, I did not really understand what my teacher meant.

‘All the letters have their own colours, though, don’t they?’ I asked in surprise. When the teacher repeated that they did not, it dawned on me for the first time that I saw language differently from the way she saw it. This was also my first conscious insight into the wonder and mystery of perception, by means of which two people can experience the same object in totally different ways.

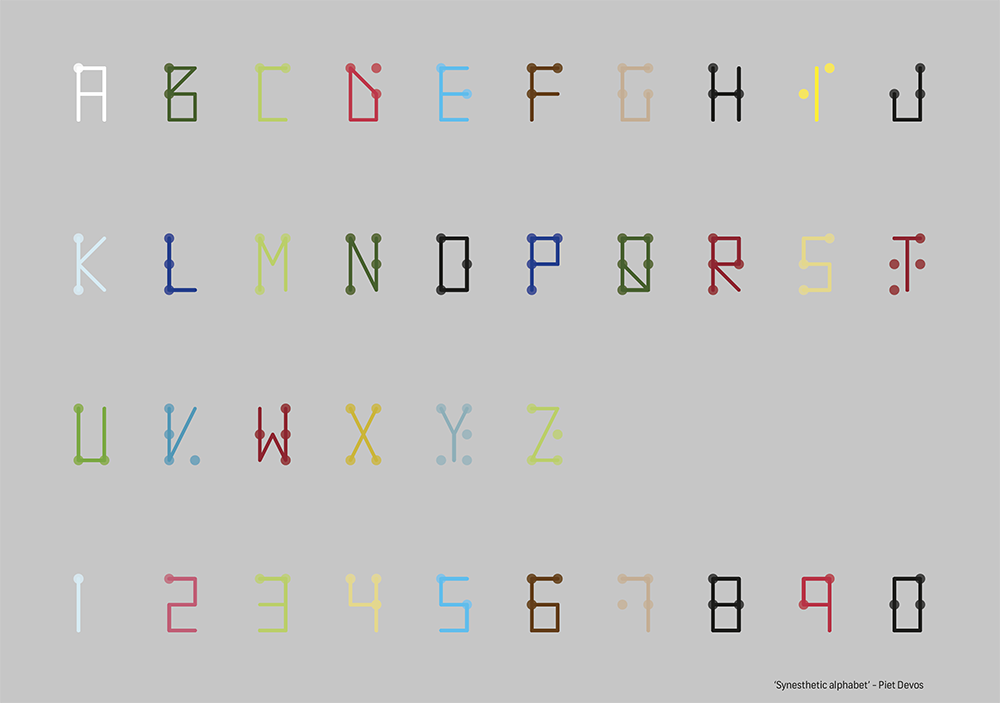

For me, it is not just each letter that has its own specific colour: the numbers, days of the week and seasons do too. These colours are relatively stable, although the colour can become brighter or duller as the sound changes. For example, ‘i’ is always yellow, but in an open sound like ‘life’ it is much more intense than, for example, the dull sound of ‘lift’. In the illustration below, you will see a representation of my colour alphabet, developed for me by the graphic designer Frea Mathijssen at my request. Please note here that I myself only see the Braille letters in my mind; the ordinary print letters have been added for clarity. What is more, although I have done my best to describe my mental alphabet precisely to Frea, the image can be no more than an approximation. After all, I cannot see and evaluate the final result myself.

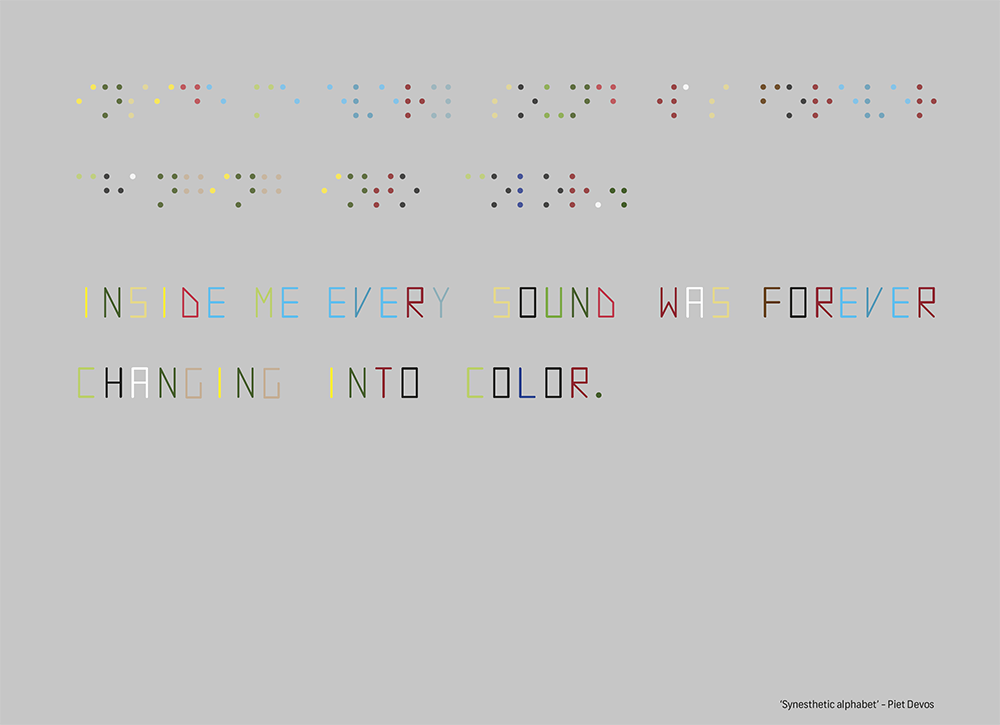

To give you an idea of how I experience reading a text, Frea has also converted a full sentence into my colour alphabet. The sentence reads as follows: ‘Inside me every sound was forever changing into colour.’ This is an abbreviated quotation from the French writer Jacques Lusseyran (1924-1971), which I feel is extremely apt. Reading Lusseyran’s autobiographical books for the first time was a rare feast of identification with his experiences. Besides going blind at a young age, as I did, he also experienced every sound as linked to a colour.

Likewise, when I listen to music, colours inevitably appear on my inner projection screen. But it is all a bit more complicated with music than with language, because the colours of music vary and blend into each other depending on the instruments used and their pitch. The piano and violin tend to be red, the trumpet and accordion are yellow and drums are white, whereas most stringed instruments evoke shades of brown and beige. The higher the note played, the more exuberant the tint, and conversely, the lower the tone, the darker the colour becomes. Where, in the opening to Mendelssohn’s violin concerto in E minor, the violin soars above everything in bright red, Bach’s first cello suite tends towards very dark grey, even black. What makes my visual experience of music even more complex is that this swirl of colours also combines with geometric planes, lines and shapes that represent the rhythm and melody. If I had any musical talent, this spontaneous visualization might be a useful study aid. Unfortunately, this is not a talent I possess. Nonetheless, the alternating colours always enrich my listening experience as a passionate music lover.

When I was a student, I found out I was not the only ‘crazy’ one whose senses are so profoundly intertwined. In psychology, this phenomenon of impressions from one sense systematically passing through the filter of another sense is known as ‘synaesthesia’. It is estimated to occur in approximately four per cent of the population, with letter-colour synaesthesia as the most common form. It is not necessarily linked to having a disability; it is quite possible that my synaesthesia is innate and was already present before I went blind. The same was true of Lusseyran, incidentally.

In other words, there are also people with good eyesight for whom hearing sounds (specifically language) is coupled with perceiving colours. Others taste their words, but this is far rarer. In 2015 I even met a perfumer in Montreal, Dana El Masri, whose perfumes are inspired by the scents that certain songs evoke in her! Whether synaesthesia provides any cognitive benefit by, for example, enabling the synaesthete to remember things better, has not yet been proved. Nevertheless, the constant creation of unexpected, sensory connections most definitely does stimulate the creativity.